After the Apartment Block

Essay by Panos Dragonas published in Domes 02/14 (May 2014), pp.20-35

Fig. 1. Thucydides Valentis, Polyvios Michaelides, Apartment block in Exarcheia, Athens, 1933-1934.

The apartment block is the dominant building typology in Greek cities. Although the first apartment blocks made their appearance in Athens in the early twentieth century, their main typological features were determined during the course of post-WWII building boom. The apartment block evolved during the period between the end of WWII and the outbreak of the present crisis. In recent years, the changes which have occurred in society and the economy have called into question the scope for the continuation of the model of urban development based on the apartment block. The debate on its “death” has already begun, (1) together with the search for a new paradigm for urban dwelling. As the history of the apartment block seems to be drawing towards its end, it is a suitable moment for a review of the basic staging-points in its development. (2) The aim of the investigation which follows is to assess the role of the apartment block in the shaping of the Greek city in the twentieth century. At the same time, it attempts to record the more modern trends in the design of buildings for collective dwellings in Greece.

Throughout the twentieth century, the development of the Greek city was in parallel with that of the apartment block. The relation between a building unit and the urban whole was determined by specific parameters which had to do with the development of the economy, legislation, and construction: the extensive sub-division of land and the existence of many owners of small lots of immovable property, in conjunction with the devising of the quid pro quo system, determined the framework of operation of the construction branch and made building one of the basic pillars of the Greek economy. In response to the general wish to acquire a home, the state supported this specific manner of development and created a favourable legislative and tax environment for private enterprise. And the introduction of the ideas of modern architecture and the ease with which the new construction principles could be implemented by non-specialist workers permitted the very rapid dissemination of the new models and produced the conditions for the “bottom-up” building of Greek cities. (3)

The first modern apartment blocks were constructed in post-War Athens a few years after the arrival of the refugees of Asia Minor. For a short period, the young architects of the time worked under exceptionally favourable conditions, as they were in contact with the international avant-garde of the inter-War years and had gained the trust of the progressive bourgeoisie of the time. (4) The principles of the modern movement were imported into Greece by way of the apartment block and answered to the quest of the bourgeoisie for a modernization of the models for living. Very soon, the adoption of modern ideas by expert engineers and contractors extended the spread of the new models into the districts inhabited by the middle economic class and led to the creation of a widely acceptable popular modernistic architecture.

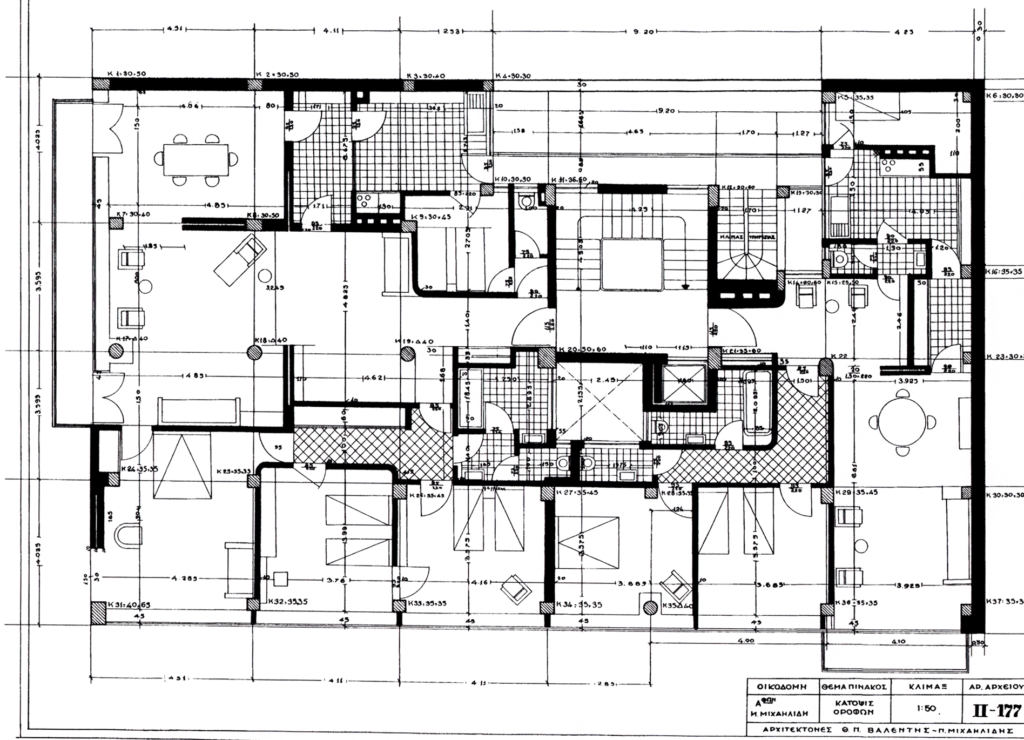

Fig. 2. Thucydides Valentis, Polyvios Michaelides, Apartment block in Exarcheia, Athens, 1933-1934. Floor Plans.

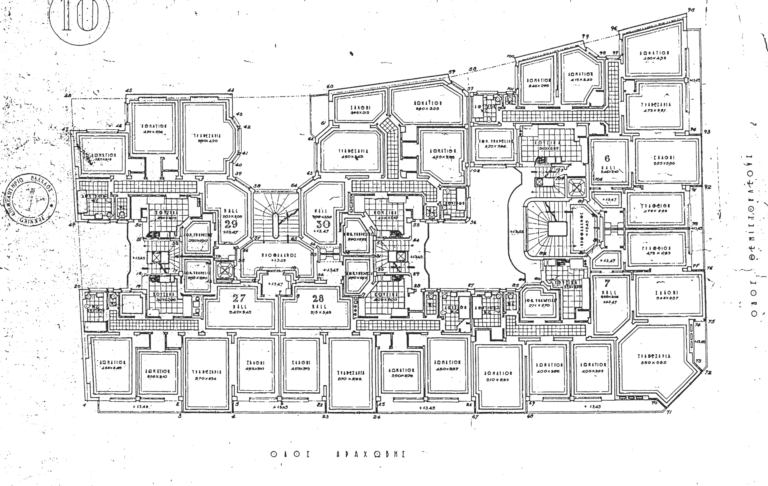

Fig. 3. Kyriakos Panayiotakos. Apartment block in Exarcheia, Athens, 1932-1933.

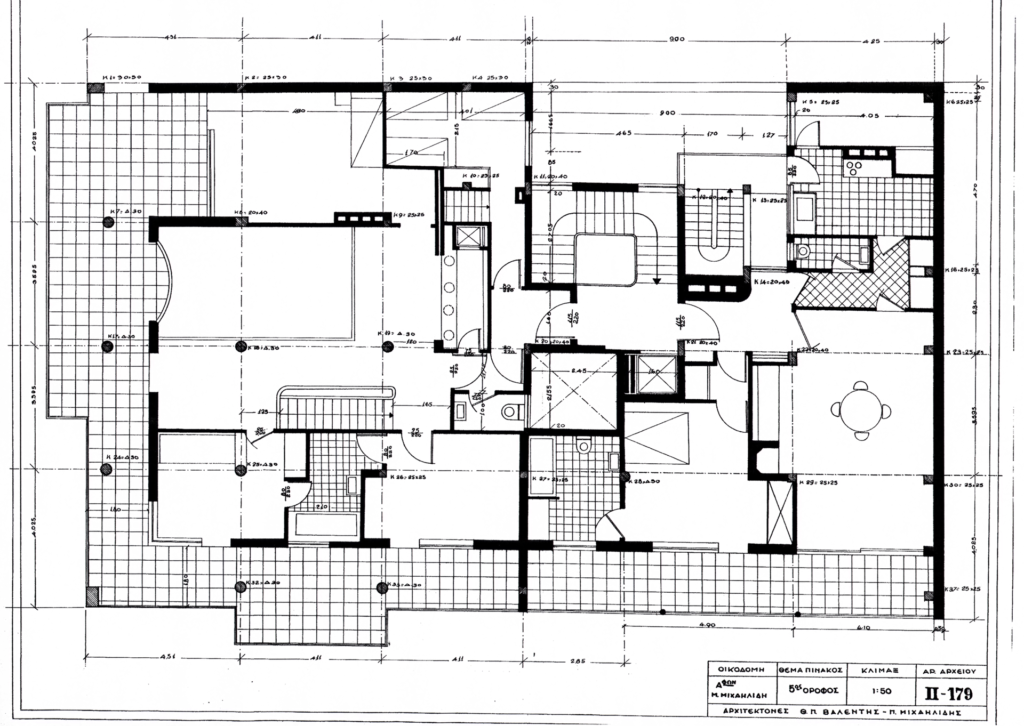

Fig. 4. Kyriakos Panayiotakos. Apartment block in Exarcheia, Athens, 1932-1933. Ground plan of typical floor.

The architecture of the inter-War years was radical in that it overturned the dominant functional and aesthetic models of Athenian society. Applied in the apartment blocks of the period were a number of the principles of Modern architecture formulated internationally at the same period, such as the linear windows in Zaimi St. in the apartment block by Valentis and Michailides (Fig.1) or the communal installations of the roof of the “Blue Apartment Block” of Panayotakos. The most characteristic feature of the inter-War polykatoikia was the freedom which prevailed in the composition of the elevations. A definitive role in their formation was played by the scope for the creation of enclosed balconies permitted by the building regulations of 1929. The imaginative compositions of enclosed and open balconies produced by the architects of the period led to different variations on relief and corrugated surfaces of buildings (Fig.3) Similarly, in the ground plans of the inter-War apartment blocks, the new models for urban living which were to dominate the subsequent decades took shape. The layout of the apartments was imbued with rationalism and marked by concern for functionality and good conditions of natural lighting and ventilation (Fig.2). Even the organization of the unimproved spaces, limited in extent, within the cities, where the service areas were located, is deserving of attention. On the ground plan of the “Blue Apartment Block” (Fig.4), a complex of hidden vertical and horizontal narrow passageways leading to tiny bedrooms can be seen. A succession of boundaries and transitional spaces isolates the areas for the stuff from the apartments of the bourgeois, thus bringing to light the social distinctions of inter-War Athenian society. (5)

The outbreak of WWII and the Civil War which followed brought about a breach in the development of Greek architecture. Migration from the countryside to the urban centers created a need for the mass production of housing for the new urban population. The greater part of these dwellings were produced by the quid pro quo system, following a “bottom-up” building process which had more in common with the way in which traditional settlements were produced than with that which created the European cities of the same period. The Greek cities were produced by the constant repetition of the basic building unit, within a loose framework of urban and street planning. The apartment block, in its turn, was produced by the repetition of the typical ground plan and the characteristic linear balconies within the strict framework of the building regulations. The design of the typical polykatoikia went no further than the implementation of certain basic principles, dictated by the limited possibilities for construction and the needs for living of the period. Basic morphological features of the anonymous architecture are the small scale, repetition, and the absence of individual initiatives in composition. In the interior of the typical apartment block, a general logic of organization, characterized by a high degree of flexibility and allowing for adaptation to differing functional requirements, was followed. Typical apartments could easily be converted to working premises for public purposes, while the ground-floor areas could accommodate commerce and the life of the street. In contrast with the logic of zoning, which prevailed at the same period in the case of European suburbs, in the Greek city, a mixture of spaces for living with commercial, working, and service premises in the interior of the basic building unit was achieved. The “osmosis” between private and public space (6) is the greatest advantage of the anonymous Athenian apartment block. The permeable shell of the building blocks, penetrated by porticos, commercial premises, areas for recreation and services, forms a basic constituent for the creation of living -and safe- cities.

Fig. 5. Nikos Valsamakis, Apartment block on Semitelou St., Athens, 1951-1953.

Fig. 6. Takis Ch. Zenetos, Margaritis Apostolidis. Apartment block on Amalias Ave, Athens, 1959-1960.

Fig. 7. Thales Argyropoulos, Constantin Decavalla. Apartment block on Deinokratous St., Athens, 1960-1962.

Fig. 8. Ilias Skroumbelos. Apartment block in Irodou Attikou St., Athens, 1970-1973.

The contribution of Greek architects to the shaping of the image of the Greek city is limited, and involves chiefly commissions from wealthy owners in central districts of Athens. The building regulations of 1955 and 1973 did not allow much scope for freedom in the modeling of building masses and the compositions of elevations. In spite of this, in the architecture of the post-War apartment block, the introduction of new morphological models and the successful adaptation of international influences to local social and climatic conditions are observable. The constant development and refinement of the new urban morphology laid the foundations for the creation of a local modern urban tradition. This involved a small circle of architects who influenced the shaping of Greek cities to a very small degree. Its importance, however, is not negligible, as it remained alive from the 1960s to the beginning of the twenty-first century. The basic constituents of the Modern urban vocabulary concerned a re-definition of the morphology of the apartment block by the use of simple geometrical features. Prominent among these were: the devising of the double elevation and the rational grid by Valsamakis in the apartment block in Ambelokipi (Fig.5); the breaking up of the solid building mass by Zenetos and Apostolidis in the polykatoikia in Amalias Avenue, where a sense of transparency and of variability predominates (Fig.6), and in the apartment block at 17 Irodou Attikou St., dominated by the horizontal and vertical surfaces; the division of the large building mass into smaller units of balconies by Decavalla and Argyropoulos in the apartment block in Deinokratous St. (Fig.7), and the morphological highlighting of the parapets of the balconies by Liapis and Skroumbelos in that in Papadiamantopoulou St., and by Skroumbelos in that at 25 Irodou Attikou St. (Fig.8).

There can be no doubt that the differences between the above paradigmatic works and the “anonymous” apartment blocks are considerable. Equally considerable, however, are the similarities which link them. The restrictions on the realisation of the works which were common to them allowed for only small steps in development and prevented radical differentiations between districts of Athens. The prevalence of a shared vocabulary with modern origins mollified the conflicts of the inter-War years and the Civil War and indicates the dominance of the new middle class which took shape in the post-War period. The very process of the production of the Greek city contributed to the creation of the subject which lived in it, as a by no means negligible part of the new urban population had taken part in the post-War building. (7) It is, then, no accident that, contrary to what one would expect, Greek cities show exceptionally limited phenomena of social division, even after the arrival of economic migrants in the late twentieth century. (8)

Fig.9. Dimitris Antonakakis, Souzana Antonakaki. Apartment block on Emmanouil Benaki St., Athens, 1973.

Fig. 10. Dimitris Biris, Tasos Biris. Apartment block in Polydroso, Chalandri, Athens, 1977-1980.

Of particular interest, from the same period, are certain isolated instances of works in which different ways of looking at the question of urban dwelling find expression. In the case of the apartment blocks of Dimitris and Souzana Antonakakis in Doxapatris St. and Benaki St. (Fig.9), the organizing principle of the pathway determines the shaping of the characteristic semi-open-air central entrance and of the interiors of the apartments. The creation of interior movements and of successive revelations of a view on to the interior of a typical Athenian polykatoikia has distinct references to corresponding attributes of spaces in traditional architecture.

As Tzonis and Lefaivre have written on the work of Dimitris and Souzana Antonakakis, “‘the pathway does not only meet a practical need… it is at the same time a comment on contemporary architecture, life, and society. It is a moral stance”. (9) Similarly, Tasos Biris, in describing the apartment block which he designed at Polydroso in collaboration with Dimitris Biris, speaks of “the image of a small neighborhood consisting of houses / cubes” (Fig.10). The design of the particular apartment block gives emphasis to the interior view, which can define “to a certain degree a specific relation of life and behaviour between its residents”, and the encouragement of an informal character in the open-air domestic spaces. (10) Apart from the reflective mood which characterizes the specific approach, the work at Polydroso is one of the very few examples in the history of Greek architecture where the apartment block is not treated as a territory of the private but as a space where social interaction is provided for.

The most important change in the development post-War apartment block has been the implementation of the new building regulations of 1985, which permit greater building heights and concede greater freedoms in the way in which buildings are sited on the plot. (11) The relaxation of the strict limitations had disappointing results as the apartment block in the quid pro quo system could not supply responses to the new design challenges. The increase in the number of floors altered the scale of the typical polykatoikia and deprived the Greek city of its characteristic feeling of “homeliness”. The break-up of the outline of the building block and the fragmentation of the Athenian skyline gave rise to a strong sense of disorder and randomness. Moreover, the influences from international post modern architecture were to lead to the appearance of a “populist” architectural morphology, of low-quality design, which would leave its mark on the identity of the new districts of the period.

Many years would have to pass for use to be made in composition of the new possibilities afforded by the building regulations of 1985. In the late twentieth century, the rates at which new building took place has slackened, as there was no longer a mass need for new homes. The economic development of the period created a demand for an enhancement of the quality of life. Albeit belatedly, the development of urban culture gave rise to interest in the city, public space, and architecture. The younger generations of architects, who have grown up in the post War urban environment, recognized the positive features of the apartment block and the Greek city. (12) The dominant trend in the architecture of the period called for a return to a simple, minimalist form of expression, with recognizable influences from the architecture of the 1960s. (13) The emphasis on the elaboration of the design of the new building subjects produced a tendency to seek differentiation from the uniformity and monotony of the generic city based on repetition. (14) As Orestis Doumanis writes, at that period, new buildings were designed “with a marked geometricality, as they attempted to establish an order which would counterbalance the chaos of the city around them”. (15) It is this tendency which characterizes works such as the apartment blocks in Pagkrati by Dragonas and Christopoulou (Fig.11), in Nea Smyrni by Nikoloutsou and Philippidis (Fig.12), and in Pagkrati by Lambrinopoulos (Fig.13). There can be no doubt that these works seek to differentiate themselves from the formless urban landscape which surrounds them. (16) At the same time, however, they give expression to the particular spirit, the contradiction, and the optimism of the period which preceded the outbreak of the great crisis.

Fig. 11. Panos Dragonas, Varvara Christopoulou. Apartment block in Pangrati, Athens, 1999-2002.

Fig. 12. Marita Nikoloutsou, Memos Philippidis. Apartment block in Nea Smyrni, Athens, 2002-2007.

Fig. 13. Constantinos Lamprinopoulos. ‘Urban Cubes’, Athens, 2009-2011.

Throughout the twentieth century, very few steps were taken in the typology of the urban apartment. An interesting typological variation of the Greek polykatoikia made its appearance in the center of Athens during the last years of this development. The introduction of new models for living is apparent in the Gazi district, where a significant number of small new apartment blocks have been constructed. Their chief characteristic is the creation of small deluxe apartments with open-plan leaving quarters and just one bedroom. The small scale of the works in conjunction with the complexity of the building design, has provided the occasion for interesting compositions, as, for example, in the case of the “Urban Lofts” of Gkikas and Filtsou opposite the old gasworks (Fig.14).

The evolution of the Greek polykatoikia was interrupted by the outbreak of the economic crisis in 2008. The current crisis has various dimensions which affect the development of cities in different ways, the main ones having to do with the collapse of the economy, social transformations, ant the threat of climate change. To begin with, the crisis has affected the construction branch and altered the ways in which the urban dwelling is produced. The new tax legislation has led to the abolition of the quid pro quo system, while the disappearance of small entrepreneurs has favoured the dominance of large, better organized, construction companies. More dramatic, however, are the transformation which have taken place in the interior of society. The dream of acquiring privately-owned accommodation has given place to the fear of confiscations. The collapse of the middle class has left its mark on the traditionally homogenous Greek city, as, for the first time after WWII, phenomena of polarisation have become apparent and tendencies towards social division have appeared. The need to deal with the problem of climate change has called into question plans for new urban expansions and has given priority to the use of the existing building stock. The changes -yet again- in the building regulation in 2012, in conjunction with the implementation of the new regulations on energy yield, have rendered necessary a re-definition of the principal design models of the Greek apartment block.

In spite of the reduction in building activity, new trends in dealing with the issue of urban housing have begun to develop in Greek cities. The most important of these concerns the need of the re-use of old buildings, which are frequently converted into housing complexes. The architecture of re-use gives rise to opportunities for the exploration of design proposals which lie outside the usual models. (17) In contrast with a modern apartment block, in the reconstructions of old buildings, the shaping of the household space does not start out from carte blanche, but incorporates features and qualitative characteristics from the previous life of the shell. Examples are numerous and involve different types of reconstructed buildings and apartments. Prominent among them are the reconstructions of two old industrial buildings (Thission Lofts and the Hub) on Peireos St. by if_Untitled architects (Fig.15), which are addressed to the young creative groups who headed to the Gazi districts during the years of the preparations for the Olympic games. There is also the recent conversion of the Doxiadis office building on Lycabettus by the Divercity team into an apartment complex (One Athens) for higher incomes (Fig.16).

In the case of last example, the construction grid is a definitive given for the layout of the new apartments. The double orientation spaces of these new apartments are a characteristic feature of the old Doxiadis building which it would be very difficult to make a priority in the design of a new apartment block. The re-use of this particular shell has become a subject of public debate because of the special architectural value of the old work.

Fig. 14. Haris Gkikas, Evangelia Filtsou. ‘Urban Lofts’, Gazi, Athens.2011.

Fig. 15. if_untitled architects. ‘Thission Lofts’, 2006-2008.

Fig. 16. Divercity. ‘One Athens”, 2007-2013.

Equally interesting, however, are the interventions made in less important old buildings, such as in an old clinic in Patras, which has been reconstructed as student accommodation by Buerger Katsota architects (Fig.17), or in an old private school on Lycabbetus which has been converted by Athanasiadou and Vasilakou (Fig.18). These interventions show the direction which the development of Greek cities will take in the future. Whether it is a case of the emblematic buildings of the 1960s or of the lowly apartment blocks of the quid pro quo system, or the scale of the single apartment, or the scale of the polykatoikia, there can be no doubt that the resourceful modification of re-use of old shells will be one of the main fields of design explorations in coming decades.

In spite of the reduction in building activity, new trends in dealing with the issue of urban housing have begun to develop in Greek cities. The most important of these concerns the need of the re-use of old buildings, which are frequently converted into housing complexes. The architecture of re-use gives rise to opportunities for the exploration of design proposals which lie outside the usual models. (17) In contrast with a modern apartment block, in the reconstructions of old buildings, the shaping of the household space does not start out from carte blanche, but incorporates features and qualitative characteristics from the previous life of the shell. Examples are numerous and involve different types of reconstructed buildings and apartments. Prominent among them are the reconstructions of two old industrial buildings (Thission Lofts and the Hub) on Peireos St. by if_Untitled architects (Fig.15), which are addressed to the young creative groups who headed to the Gazi districts during the years of the preparations for the Olympic games. There is also the recent conversion of the Doxiadis office building on Lycabettus by the Divercity team into an apartment complex (One Athens) for higher incomes (Fig.16).

In the case of last example, the construction grid is a definitive given for the layout of the new apartments. The double orientation spaces of these new apartments are a characteristic feature of the old Doxiadis building which it would be very difficult to make a priority in the design of a new apartment block. The re-use of this particular shell has become a subject of public debate because of the special architectural value of the old work.

Equally interesting, however, are the interventions made in less important old buildings, such as in an old clinic in Patras, which has been reconstructed as student accommodation by Buerger Katsota architects (Fig.17), or in an old private school on Lycabbetus which has been converted by Athanasiadou and Vasilakou (Fig.18). These interventions show the direction which the development of Greek cities will take in the future. Whether it is a case of the emblematic buildings of the 1960s or of the lowly apartment blocks of the quid pro quo system, or the scale of the single apartment, or the scale of the polykatoikia, there can be no doubt that the resourceful modification of re-use of old shells will be one of the main fields of design explorations in coming decades.

In spite of the outbreak of the economic crisis, the shaping of new models for living and the introduction of new design models are continuing to affect the development of urban housing. In contrast with the typical post-War apartment block, which responded to the needs of the nuclear family, providing formal layouts with two or three bedrooms, at the present time, examples of apartment blocks addressed to special groups, to students, for example, or responding to lifestyles which do not follow the usual conventions, (18) are on the increase. A typical example is the winner of the first prize in the competition for the design of a polykatoikia for students in the Metaxourgeio district (18 Steps) by FORA, where the tiny student apartments extend in to an interior communal space for study and social gatherings (Fig.19). New examples of luxury constructions addressed to upper income brackets and providing extra benefits and services, such as Oyster Smart Flats by ISV architects, are making their appearance (Fig.20). At the same time, a need for innovative design approaches which break away from the modern tradition and the more general aesthetics of the post-War apartment block has been identified. The policy followed by private companies which are active in the central districts of Athens is typical. A first example is provided by the work of Papadopoulos and Daskalakis on a housing complex in Metaxourgeio which introduced new models for living into the area, while at the same time bringing back typological characteristics of traditional Athenian architecture, such as the central courtyard. More radical, however, are the ideas introduced by the private KM Properties project for the remodeling of the Kerameikos and of Metaxourgeio.(19) A basic constituent of this particular urban development programme is the creation of a contemporary architectural identity for an area by means of the contribution of prominent international architects (such as BIG and Atelier Bow Wow) (Fig.21).

Fig. 18. Angeliki Athanasiadou, Katerina Vasilakou. ‘Re-experiencing/ Re-vitalising 48A Dafnomili’, Athens.

Fig. 19. FORA, Oliveira, Ruivo Architects. ’18 steps’, 2009

Fig. 20. ISV Architects, ‘Oyster Smart Flats’, Athens.

The introduction of new lifestyles and the adoption of new design models are positive, and to a large measure expected, developments in a developing city. Athens is no longer the homogenous city of the post-War period, but a multicultural megalopolis with different faces and major contrasts. The intensifying social polarisation is reflected in the urban space and in the evolution of the dwelling. The generic architecture of the Athenian polykatoikia is no longer capable of alleviating the social conflicts created by the evolving collapse of the middle class. This is the end of the post-War apartment block, the end of the generic city of repetition, and also the end of the subject which has dominated throughout the post-War period. The change of paradigm which is taking place in the manner of development of the city involves many dangers, and calls for serious measures to avoid social division and the safeguarding of urban diversity.

The experience of the post-War Greek apartment block is particularly instructive and may prove beneficial in the determination of new principles for the shaping of housing areas. The adaptation of the modern language of architecture to local particularities and its adoption by unofficial urban planning have supplied a solution to the problem of mass production of housing by providing adequate conditions of public health and security. To an even greater degree, the flexibility of the typical apartment, the “osmosis” between the public and the private space in the interior of the apartment block, and the “bottom-up” building strategy are the basic constituents of a successful recipe for creating living cities, without problems of social division. The general prevalence of the modern urban vocabulary has led to the establishment of “common ground” in Greek cities. The modern apartment block was an expression of modernity and progress during the inter-War period and the early years of post-War building. It developed into an urban tradition in the late twentieth century, while more recently it has been turned into an object for conservation and re-use.

The conditions which led to the creation and development of the Greek apartment block are today a thing of the past. However, the study of the apartment block as a model unit for urban dwelling still has much to offer to Greece and to the world at large. It is, in any event, no accident that there has been international interest in the apartment block and the Greek city in recent years. Greek cities are structured to a very large degree by apartment blocks, which are exceptionally difficult to replace by new buildings of a different typology. What is most probable is that in the future the main concern of architectural design will involve reconstruction of the shells of existing apartment blocks. It is extremely likely that in the future new typological mutations of the Greek apartment block which will supply answers to recent social, cultural, and environmental demands will make their appearance. In one way or another, the polykatoikia will continue to claim our attention. Whether as an object of research, or as a subject of re-use, or as a typological development, the apartment block will remain the basic shell of the Greek city for many years to come. The polykatoikia -as we knew it- is dead. Long live the polykatoikia!